Building Roads with Music

Musician and professor Kojiro Umezaki builds connections between communities

By Christine Byrd

Kojiro Umezaki plays a traditional Japanese bamboo flute called shakuhachi, which has been around for centuries. But he also uses artificial intelligence to analyze and layer recordings of himself playing the instrument. Bringing together ancient and modern, natural and digital, East and West, are central to Umezaki’s creation of hybrid music and his teaching as a professor of music in UCI’s Integrated Composition, Improvisation, and Technology program.

"Through music, we can explore ways in which [ancient and modern] coexist and dialogue with each other.”

“Hybrid music can be anything where you mix two things that don’t seem like they would naturally come together,” Umezaki says. “If you think of the shakuhachi as embodying centuries of older knowledge, and computers as creating new kinds of knowledge, they seem to exist in two different spaces. Through music, we can explore ways in which they coexist and dialogue with each other.”

It’s a dialogue Umezaki brings not only to UCI students but to K-12 students at schools across the country, including one located in a remote Indian reservation in Montana, where he’s been visiting and teaching for over a decade.

A Meaningful Life

To explain his interests, Umezaki talks about his parents and World War II. His Japanese father had witnessed the mushroom cloud created by the atomic bomb the U.S. dropped on Nagasaki, from his hometown across the bay. Meanwhile, his Danish mother lost her father to the fighting. The unlikely pair met in a Spanish class at a small college in Ohio after the war, where they were international students from opposite sides of the globe.

The couple settled in Tokyo, where Umezaki and his brother were born. Because of his mixed race, Umezaki felt like he didn’t fit in in his homeland. Looking back now, Umezaki thinks he may have been drawn to the shakuhachi – a musical tradition typically passed down from generation to generation — as a way to reinforce his Japanese identity.

Like his parents, Umezaki came to the U.S. for college. In graduate school at Dartmouth, he was mentored by pioneer of electro-acoustic music Jon Appleton, and that relationship cemented his interest in a career in academia.

“I saw in him someone who had a life that was very meaningful,” says Umezaki, who joined UCI faculty in 2008, when the Integrated Composition, Improvisation and Technology program was brand new.

“When I found out what UCI was trying to do with ICIT, I knew it could have a lot of impact,” he says. “I felt really lucky.”

Image: Umezaki (second from left) with members of the Silkroad Ensemble on the summer 2022 Phoenix Rising Tour.

Silkroad

In 2001, Umezaki got a call asking if he could play a piece written for shakuhachi and cello written in a style that reflected “the Japanese response to European modernism after the war.” After he agreed, Umezaki discovered the musician he would be performing with was internationally acclaimed cellist Yo-Yo Ma.

Thus began Umezaki’s two decades of work with Silkroad, a collaboration of international artists who perform and teach with an emphasis on using arts to build bridges and foster connection across cultures and geographic boundaries. Silkroad has taken Umezaki to perform and teach around the world, including at high-need schools in Chicago, Iowa and Montana.

“It’s a way to engage with students using the arts as a catalytic force toward being more engaged and passionate about learning,” he says. Studies have shown arts programs like these can increase school attendance and academic outcomes.

Image: Umezaki plays for students as a part of the Kennedy Center’s Turnaround Arts program, supporting under-resourced communities (Photo: Kyle Knicley | Des Moines Public Schools).

On the Reservation

Lame Deer High School is about 100 miles east of Billings, Mont. on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation — where the life expectancy is nearly 20 years less than the U.S. average. The school was among eight selected by the President’s Committee on the Arts and the Humanities during the Obama administration to pilot the Turnaround Arts Program, aimed at improving underperforming schools through arts.

Blank stares and confused looks from the students greeted Umezaki and his fellow artists on their first visit. But they kept going back year after year — even after the federally funded pilot ended and Silkroad took the project under its umbrella. The ensemble performs and works with students on projects that incorporate music, dance and storytelling. They even cook side by side, the visiting artists preparing homemade ramen while the students make Indian tacos from scratch, sharing their cultures through food.

“It’s made such a strong impression on me, because it’s hard to get there to visit, but it’s even harder for the young people to leave the reservation, for other reasons,” he says. “I hope that we can make the boundary between local and global a little more porous.”

A decade in, Umezaki can see some changes taking root. Two Lame Deer students recently wrote lyrics in English and in Cheyenne, which a small group then recorded in a studio in Bozeman, Mont., while Umezaki joined them in the studio via Zoom. A digitized version of that song is going to the moon — literally — on a rover, through a collaboration with Montana State University. This spring, a small group of Lame Deer students will visit UCI, with plans to shoot a music video to go with their song.

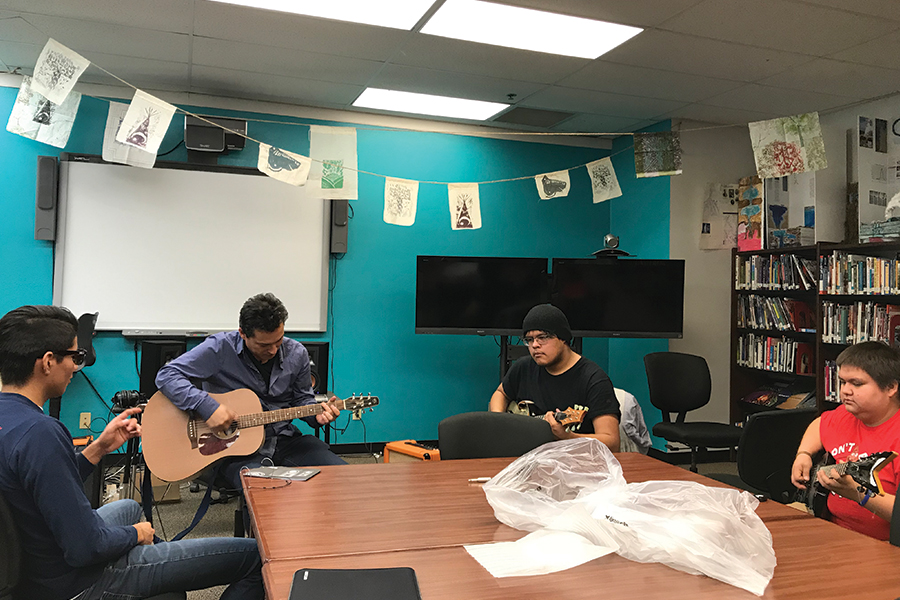

Image: Umezaki works with students from the Lame Deer High School on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation, about 100 miles east of Billings, Mont.

A Destination

Umezaki hopes to continue planting seeds of inspiration and hope with the students, using art for the dual purposes of gaining freedom, and feeling grounded.

“Silkroad is about opening up dialogue while maintaining a sense of who you are and your traditions,” he says.

Umezaki wants both his students at Lame Deer and at UCI to see their own traditions and cultural practices represented – or feel comfortable creating something entirely new.

“We’re led to believe that certain kinds of music making, like classical music, are at the top of the pyramid,” says Umezaki. “But we have so many different kinds of voices in music making that are at an extremely high level of skill and artistry, so why can’t they be at the top of the pyramid as well?”

Umezaki hopes to see a Lame Deer student attend college at UCI and for the Claire Trevor School of the Arts to be recognized as a school that attracts students from a variety of cultures and artistic traditions.

“I hope we can create the infrastructure for artists who have different voices, who look differently, talk differently, eat differently, to see UCI and CTSA as a destination, one where students’ past and future coexist in conversation with each other.”

To learn more about faculty in the Department of Music, visit music.arts.uci.edu.

To learn more about Kojiro Umezaki's professional work, visit his website at kojiroumezaki.com.

Please visit our secure direct giving page and make a gift to support Music today!