Alumni Profile: A Conversation with Glenn Kaino

Professor of Art Simon Leung chats with Glenn Kaino (B.A. ’93), an artist who’s been at the intersectional forefront of art and activism for more than two decades. Known for his conceptual, activist, and frequently collaborative multifaceted art practice, Kaino occupies a unique place in the art world and beyond.

Simon Leung: Tell us about your time at UCI.

Simon Leung: Tell us about your time at UCI.

Glenn Kaino: UCI was a magical place. I had the fortune to go there in the 1990s when Catherine Lord was transforming the Art Department into the most diverse and impactful team of artists and scholars. The new faces of diversity (Daniel Joseph Martinez, Ulysses Jenkins, Connie Samaras, Karen Carson, Judy Baca, Catherine Opie, Pat Ward Williams and others) were just charging! The undergrads would hear stories about classes and teachers, and the ideas they were championing, and it felt alive. I transferred in and not knowing any better, set up meetings with every teacher to introduce myself, and met all the student studio rats that were always around and connected with everyone; and ended up helping to create a really productive chemistry during my time there. We self-organized events like an artist basketball league and a drag prom; I organized a group to create a departmental print magazine and the first-ever digital ’zine, and we created a real exhibition series. The byproduct of my time there was that I left with the absolute belief that art was important and could exist as a generative form of scholarship.

SL: In the 1990s you co-founded Deep River, an alternative space in downtown LA with UCI Prof. Daniel Joseph Martinez, Tracey Shiffman, and Rolo Castillo. Would you talk a bit about that?

GK: Deep River was a space for experimentation and change. It was a five-year plan and we aimed to champion artists we felt deserved a moment. We had just a few important ideas going into it and we stuck with them. In the beginning we decided that we were going to save our money to make a gallery that was as high-quality as a museum. Operationally, we had a strict budget: $600 per opening—$200 on stamps, $200 on invitations, and $200 on drinks; we were only open on weekends, and we didn’t sell art. Most importantly, on the front door there was a small line of type that read “No Critics Allowed.” We didn’t want to participate in what we felt to be a rigged system of validation that prioritized an exclusionary art world value system. There were hundreds of people at each opening, and we created a “Deep River Family.” At the time, the “Art Center Mafia” as we called them spawned China Art Objects, a commercial gallery. UCLA was very tied in to MOCA, and Cal Arts was everywhere, but nothing much existed for UC Irvine. We hosted annual exhibitions for UCI students, and several of our exhibitions were of artists associated with the program. There were some historic standouts, like Mark Bradford’s first exhibition, Diane Gamboa, and the Domantay Brothers’ opening boxing match.

SL: Last year I went to see two shows of yours: When A Pot Finds Its Purpose at BAM in Brooklyn, and With Drawn Arms at the San Jose Museum of Art, part of your continuing collaboration with the Olympic gold medalist and civil rights hero Tommie Smith (immortalized for the Black Power salute in the 1968 Summer Games). Both were politically engaged, but different: The first was a kind of political theory in situ through figures of nationalism and patriotism (e.g. American Flag, Liberty Bell). The second resembles an alternative or anti-monument...

GK: A central premise of my studio is that to make ideas relevant, we approach everything from multiple angles. In the case of the show at BAM, I was inspired to present works that asked big questions about the state of our democracy while simultaneously offering a critical examination of how systems of symbolic representation and power are out-of-date, but doing so within a framework of hope and inspiration. Rather than dissect a problematic moment as would a scholar, I attempt to frame the overall crisis within a larger, poetic time scale, allowing for the possibility of recovery and transformation in ways that aren’t encumbered with cynicism or desperation. With Drawn Arms is a form of praxis. I am still engaging in questions about patriotism, nationalism and a critique of institutional racism, but in an active way — with my work creating conceptual pathways for me to be an active agent. The story of the works in the exhibition are documented in the upcoming film of the same name, so an even larger audience than the museum-going public will see how art can play a reinvigorating role in repairing cultural damage. Art that is visually compelling creates an abstract epistemological space where new ideas can be learned and absorbed in non-didactic ways. Seeing something amazing and being inspired into action is what that’s all about for me.

SL: Your work demonstrates a deep commitment to racial and social justice, an honoring of Blackness, and a fight against anti-Black racism. Talk a bit about your work as an artist and activist?

GK: My work attempts to engage an intersectional set of concerns from both social justice and climate justice perspectives. I have been dedicated to fighting against inequality from a young age, with foundational experiences in elementary school all the way through to crafting an intellectual framework as an undergraduate at UCI and in grad school at UCSD. A big part of my effort has indeed been in direct support of fighting anti-Black racism and learning from and working with African American activists and scholars, from Congressman John Lewis and Tommie Smith, to Nelson George and Oprah Winfrey, to my frequent collaborators Jesse Williams and Deon Jones. Discriminatory systems work against all marginalized groups and there is no singular methodology to help make change. But by focusing much of my effort as you say, to honor Blackness and fighting anti-Black racism, I try to prioritize contributing to what I believe to be the most urgent concern in social justice in this country, the violence and discrimination against Black Americans, and also model a needed form of solidarity by creating ad hoc coalitions from my position as an Asian American. We must fight for each other, with each other, and know that when we do so, we are also fighting for ourselves.

SL: 2020 is what I think of as “The Great Reckoning.” Many people are now talking about issues your work has been engaged in for years. What are your thoughts on this?

GK: Don’t call it a comeback, I’ve been here for years! Ha! In seriousness though, I have to say that I was fortunate to have been inspired by the unique cast of artists and scholars at UCI that inspired me and gave me confidence to create a practice in support of my world view. I joined their party, and they joined the party from the generation before them. This Great Reckoning might be an even bigger expansion of the dialogue and hopefully our work collectively inspires the next generation of artists to keep pushing harder to fight for a more just world.

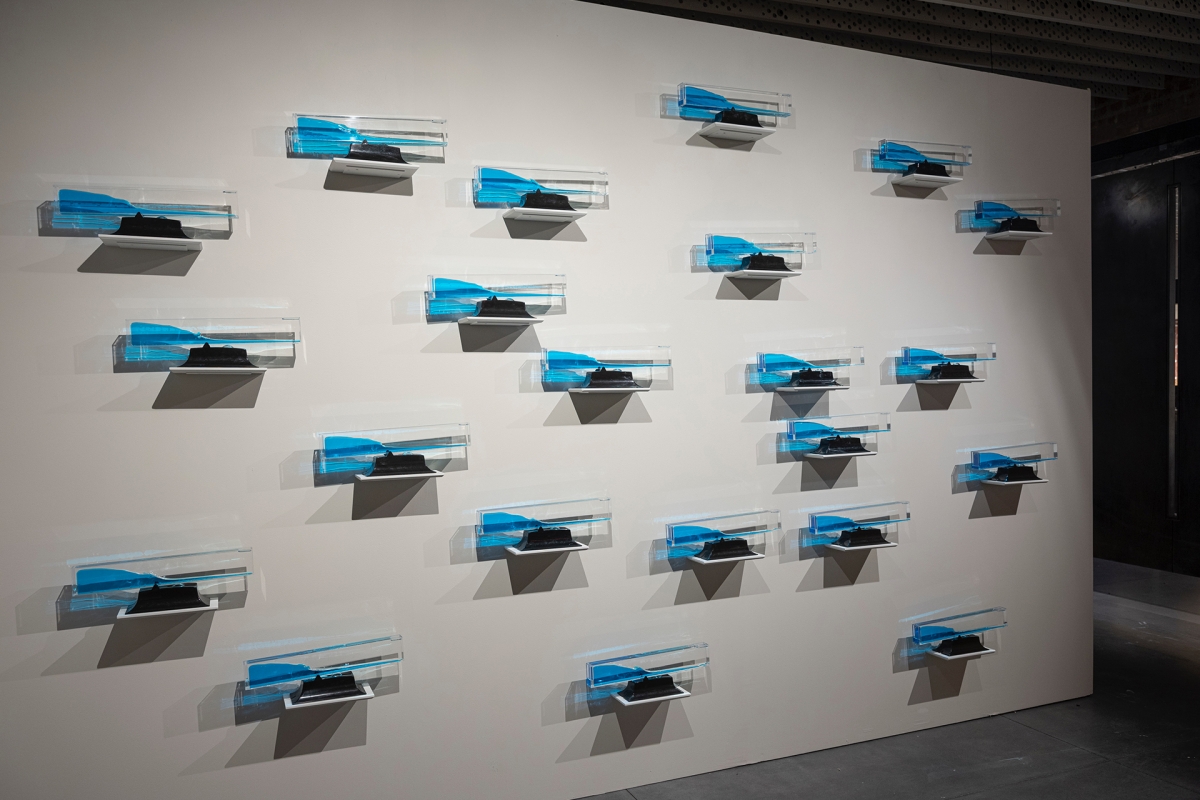

Images: (top) Glenn Kaino, Photo: Brian Gaberman. (bottom) Glenn Kaino, “Blue,” 2000, Wave machines, wood shelves, and calibrator. Installed at BAM (Brooklyn Academy of Music), Brooklyn, NY.

To learn more about Glenn Kaino and upcoming exhibitions at glennkainostudio.com.

Please visit our secure direct giving page and make a gift to support Art today!